This excerpt is taken from Ted Widmer’s Brown: The History of an Idea, “Brown Begins,” Chapter 1, released on May 7, 2015, in conjunction with Brown’s 250th Anniversary.

… While a number of locations for the college were proposed — another place in Bristol County, or East Greenwich — the question soon turned into a contest between Rhode Island’s two principal towns. For some time, the rivalry between Newport and Providence had flavored local politics, with clan-based struggles over legislation pitting Providence and Newport families against one another.

Over the fall and winter of 1769, the battle raged. In November, a local observer listed the criteria for selection. The site should be in a place where the air was clean and “not subject to epidemical disorders,” and it should be in a location that was morally uplifting, if it was possible to find one in Rhode Island. He added that it should be a place of tolerance, in the Rhode Island spirit, open to a variety of denominations. It should have good transportation. And it should be a place of diversion and diversity, “so that the students may become acquainted with men as well as books, that when their academical studies are finished, they may not be finished blockheads.” 77

The site should be in a place where the air was clean and “not subject to epidemical disorders”

At first, the odds were in Newport’s favor. Roughly twice the size of Providence (with a population of 8,000, compared with 4,000), it was a bustling entrepôt of culture and commerce, closer to the broad Atlantic, the source of the trade that brought the latest books, ideas, and luxury items to upwardly mobile Rhode Islanders. Indeed, in Newport’s glory years of the mid-eighteenth century, its foreign trade exceeded New York’s. It possessed a warm spirit and a warm climate as well — as the historian Carl Bridenbaugh wrote, its weather was “one coat” warmer than Boston’s, and perhaps a shirt warmer than Providence’s. Its intellectuals were impressive — not only Ezra Stiles, but also Samuel Hopkins, a prominent disciple of Jonathan Edwards (and an important opponent of slavery). Newport’s culture of tolerance rivaled that of any other place in America. Its culture of knowledge was impressive as well, and the Redwood Library and Athenaeum held a significant collection of books and art, far more magnificent than anything in Providence. The latter place was still known for some religious looseness. A wandering Harvard graduate, Jacob Bailey, sniffed: “the inhabitants of this place, in general, are very immoral, licentious, and profane, and exceeding famous for contempt of the Sabbath.” 78

But Providence was coming up very quickly at precisely this moment. Whether one studies the old court records, the architectural legacy, or fictional accounts such as H. P. Lovecraft’s The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, one senses a city teeming with energy, new wealth, and ideas. Indeed, the American Revolution would soon confirm that Providence, not Newport, was Rhode Island’s center of resistance to the British Crown.

Providence, not Newport, was Rhode Island’s center of resistance to the British Crown.

Providence was also emerging as a place of writing and publishing. Its library was not insignificant, and it too had a cluster of intellectuals — rising men of science as well as business (often a thin line separated the one from the other). If there was a single academic discipline in which the Brown family had excelled during its rise to power, it was mathematics — their business records contain extraordinary cipher books in which they did their prodigious accounting.79 Joseph Brown, in particular, was experimenting along scientific lines, trying to cheat nature of her secrets. With his deep knowledge of the relatively new subject of electricity, he must have struck some of his townsfolk as a kind of wizard. In many ways, the four brothers were avatars of modernity, learning to build with new materials such as iron and glass, and bringing the latest technical knowledge of machinery and motive power. It is noteworthy that the Browns, unlike Newport’s grandees, were at this time expanding their business into manufacturing (they launched their pig-iron works at Hope Furnace in 1765).80

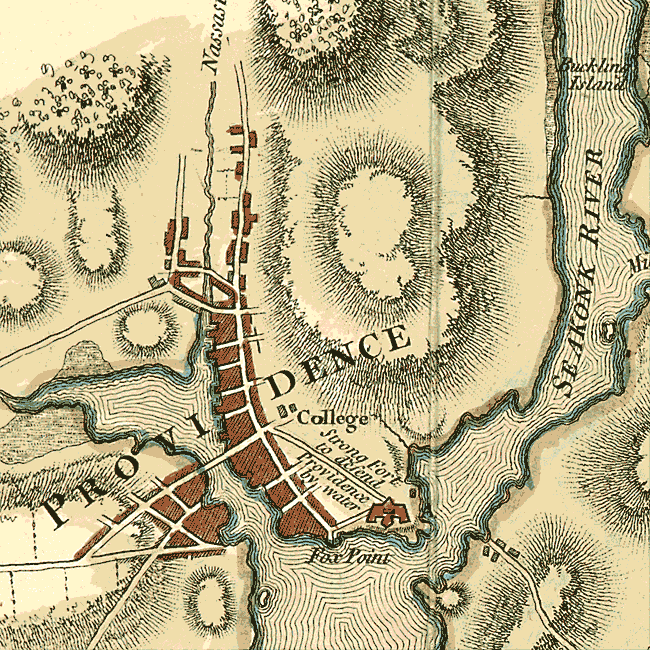

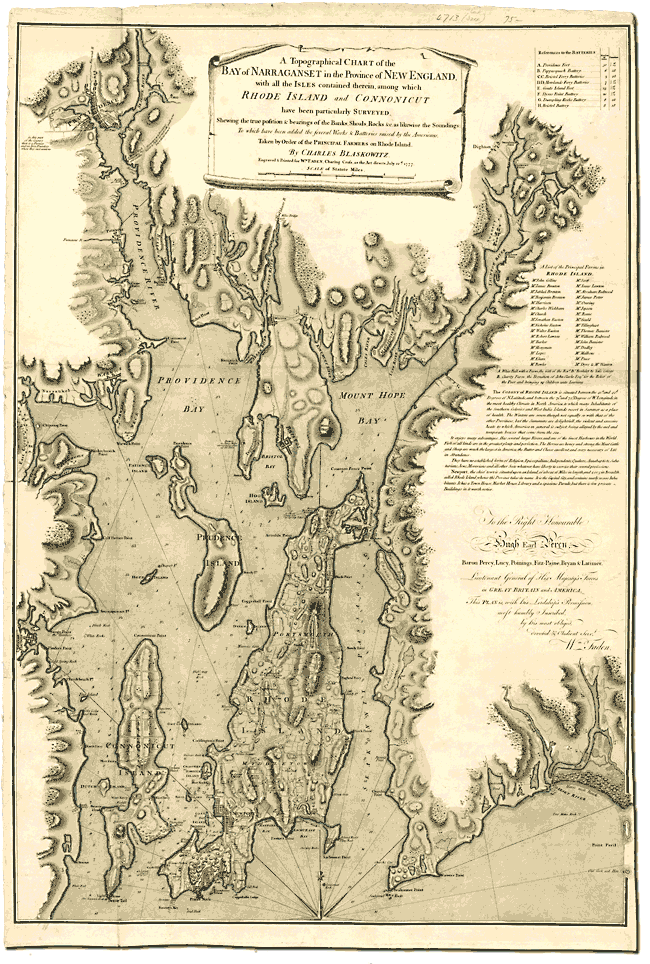

This map is excerpted from the larger map below. It was drawn by a British military surveyor, Charles Blaskowitz, and published in London in 1777. The excerpted section includes the identification of "College" which is believed to be the first and therefore, earliest representation of Brown University on any map.

Providence also had more Baptists than Newport. Significantly, it had the tacit support of the college president, Manning, who apparently directed traffic throughout the contest, advising the friends of Providence on how to approach the Corporation …

The meeting that finally decided the issue was held February 8, 1770, at Warren. Stephen Hopkins made the closing argument for Providence, and the Browns were out in force, lobbying and helping to sweeten the financial offer. The amounts raised by Newport and Providence were similar — but also hard to measure, for each side was indulging in creative math, counting pledges and hints of pledges to come.87 Isaac Backus wrote in his diary, “Both sides shewed such indecent heats and hard reflections as I never saw before among men of so much sense as they, and hope I never shall again.”88 But finally it came down to a vote, and Providence prevailed, 21–14. It would never be the same city again. The Browns had done their work well.

The Publication Brown: The History of an Idea, is available exclusively at the Brown Bookstore through Fall 2015 and at national retailers following. Purchase in store, online or call (401-863-3168).

Ted Widmer served as the Assistant to the President for Special Projects at Brown University and the Beatrice and Julio Mario Santo Domingo Director and Librarian of the John Carter Brown Library. From 2012 to 2013, he also served as a senior adviser to Secretary of State Clinton. He has written or edited many works of history, including Ark of the Liberties and American Speeches (Library of America).

Notes from Excerpt

78. Kimball, Pictures of Rhode Island in the Past, 56, 72.

79. Hedges, The Browns of Providence Plantations: Colonial Years, 6, 10.

80. Ibid., 15, 123. This iron would be useful during the American Revolution, when it was used for cannons.

87. Guild, citing Manning, in his Historical Sketch of Brown University, calculated the amounts as £4,280 raised by Providence, £4,000 raised by Newport (125).