From the 1770 College Edifice (now University Hall) to the fragments of historic glass bottles and porcelain plates now buried in campus soil, all physical reminders of Brown University’s long history are all around us. In recent years, undergraduates in the “Archaeology of College Hill” course, offered by the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World, have surveyed and excavated College Hill to learn more about its rich history and to find material traces of its past. Students previously worked off campus at the First Baptist Church and the John Brown House, but more recently they have investigated Hope College and the site of the first President’s House.

Hope College, built in 1822, is the northernmost building on the Front Green. It has been a dormitory for its entire history. In 2012, the “Archaeology of College Hill” class opened up two trenches along the building’s western face. The first contained many small objects discarded by Brown students long ago, including glass bottle fragments and sherds of porcelain. Surprisingly, the class also uncovered several bullet casings! The second trench, located in front of the doorway, revealed traces of stone paths formerly leading to the building.

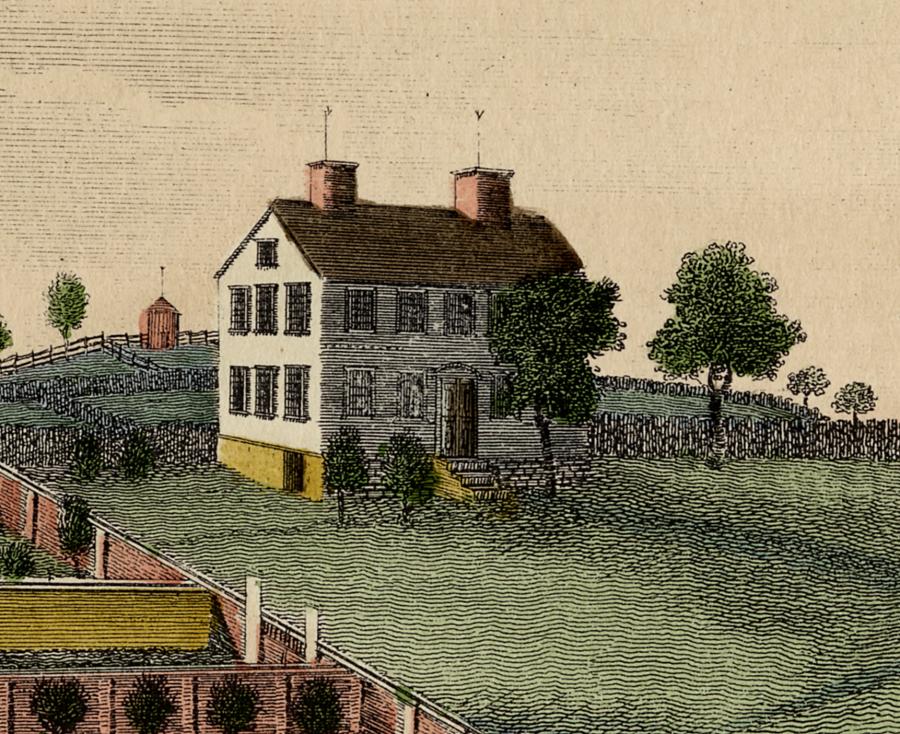

In 2013, the class turned its attention to another significant building from Brown’s early history: the first President’s House. Constructed on the Front Green in 1770, the same year as the College Edifice, it was removed in 1840, when a new President’s House was built at the corner of College and Prospect Streets (today's President's House at 55 Power Street was purchased by Brown in 1947). A commemorative plaque on the gate just west of Carrie Tower reads:

“Near this location was the first official residence of the president of Brown University”

So, in the fall of 2013, the "Archaeology of College Hill" class set out to rediscover the house’s original location. Historic documents and paintings gave some general clues, but the students analyzed the results of the 2012 ground penetrating radar survey to pinpoint its location. Then they excavated two trenches northwest of University Hall, on a site where the geophysical survey revealed the possible foundations of the house’s walls.

The excavations of both trenches produced numerous archaeological materials attesting to the long history of use of the Front Green, from Brown’s earliest days to the present. Bottle caps, glass bottle fragments, pull tabs and sherds of ceramic mugs were unearthed. Also uncovered were pens, pencil lead and even a small metal jack—tools and toys demonstrating that students worked and played on the Green in the past, just as they do today. Several other interesting objects turned up, most notably a large skeleton key, which is currently being cleaned and conserved for further study.

Were any traces of the President’s House found? Possibly. Both trenches contained vast quantities of broken red bricks as well as some fieldstones, both of which could have been building materials for the original house—or for a later construction. While most of the ceramic dates to the 1800s and 1900s, beautiful pieces of yellow Staffordshire slipware from the late 1700s were found—the exact period when the President’s House was constructed.

While these building materials and early pottery could be clues that the dig is on the right track, future students in the “Archaeology of College Hill” class will have opportunities to dig deeper and perhaps at last confirm the location of this important building in Brown’s history.