Brown University, founded by 18th century Baptists, exhibited a rare tolerance for often competing religious views. The University’s founders, however, could not have imagined the diversity that characterizes Brown today.

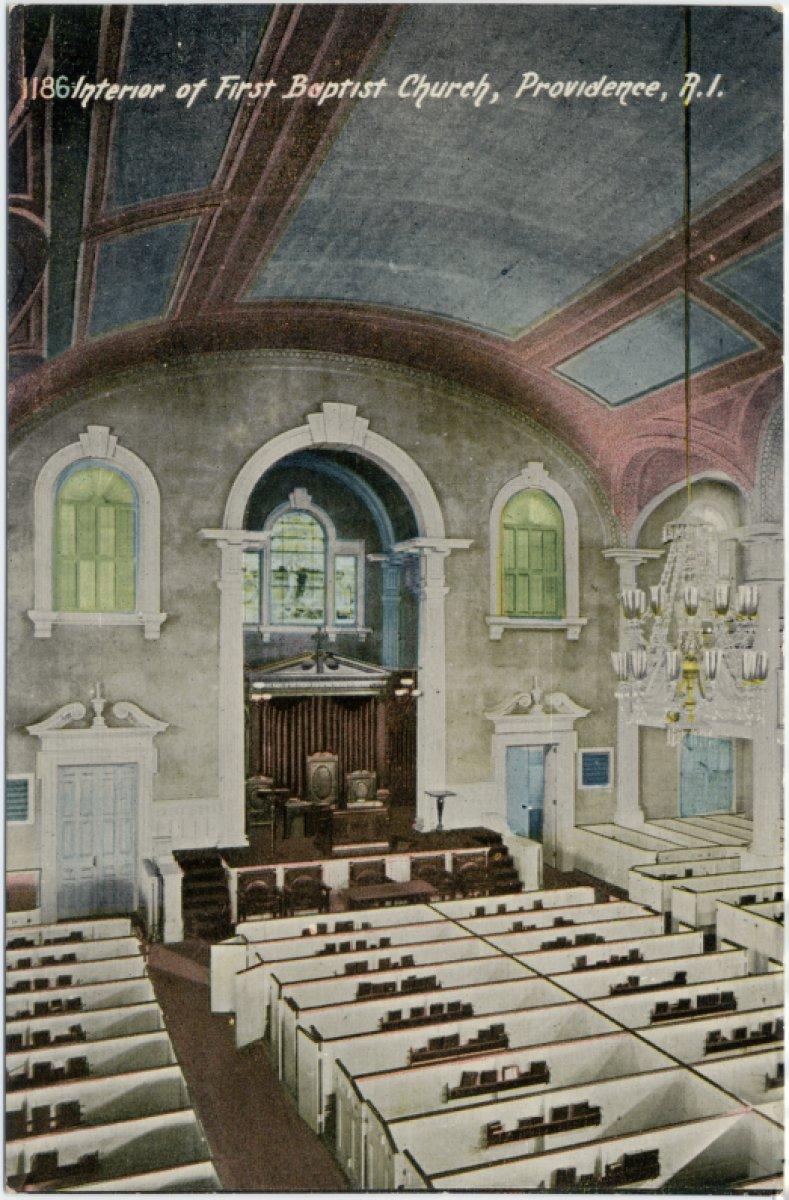

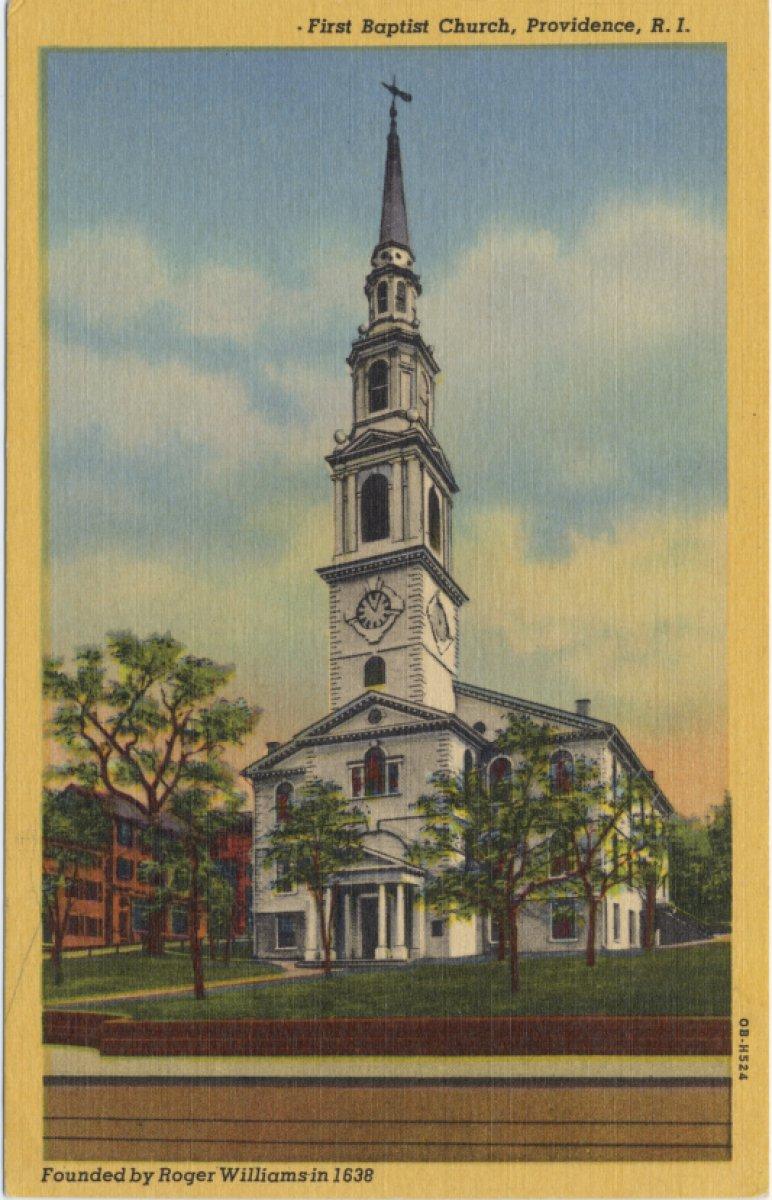

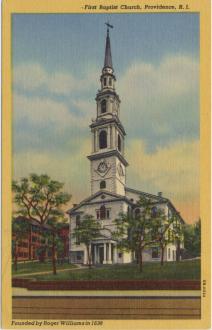

Perhaps no ceremony bears witness to the dramatic changes in the campus community better than the annual Baccalaureate held every May in conjunction with the Commencement ceremonies. Honoring the ancient custom of graduates receiving the laurels of oration from distinguished voices delivering Baccalaureate addresses, the service in the modern era has featured Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, John Hume, Bill Moyers, Shiran Ebadi, Dave Eggers, Gustavo Guittierez, David Rohde and the Aga Khan to name only a few. An over-capacity crowd gathers in the First Baptist Church and the service is broadcast to thousands on the College Green and beyond. Baccalaureate’s layers of language, prayer, dance and song articulate the grateful, multilingual prayers of Brunonians and provide a sacred glimpse for our next 250 years.

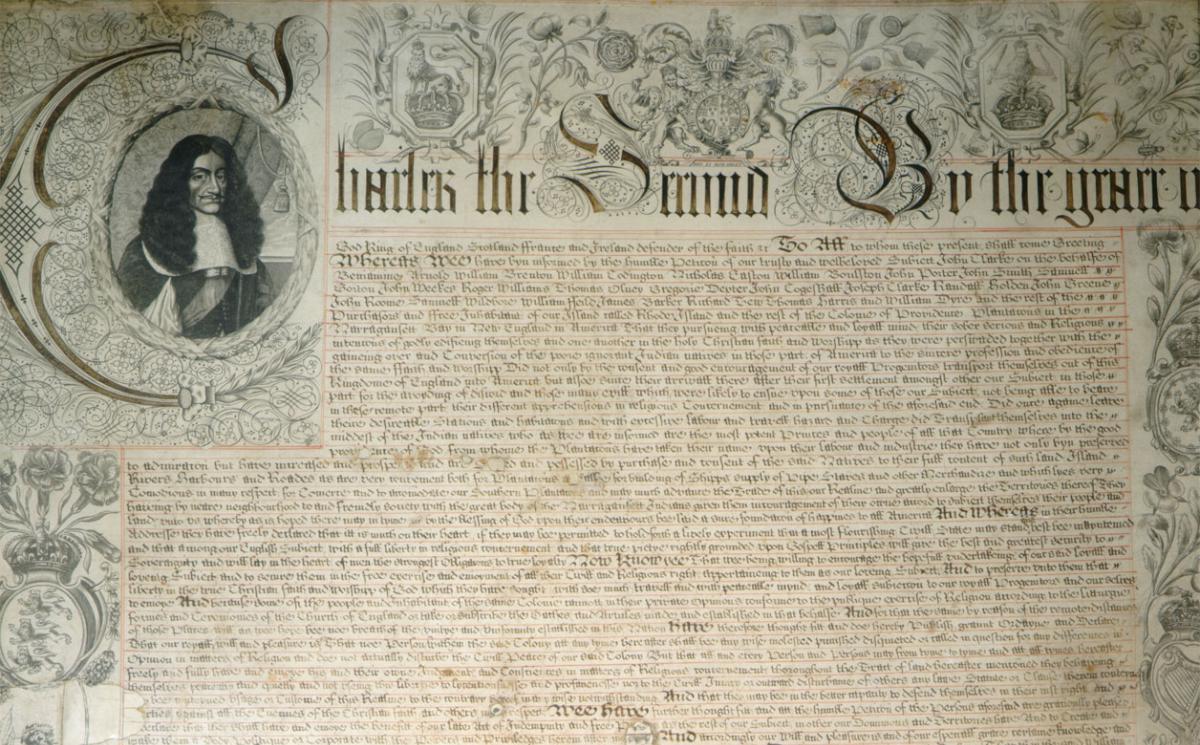

The University’s Charter laid the groundwork, uniquely declaring no religious affiliation; forbidding religious tests in admission; stipulating that trustees of Episcopal, Congregational and Quaker background would join the Baptists to govern; and obliging the curriculum to examine all moral questions—concerns then as varied as slavery and universalism, a hotly contested notion of the day about who could gain salvation.

In 1826, universalism was at the heart of President Francis Wayland’s plan to address campus rowdiness, misconduct he blamed on President Asa Messer’s doctrine of universal salvation—with no eternal punishment for sin. Wayland’s stern Chapel talks, along with better dormitory proctoring and diminished supplies of beer and cider, dramatically improved student conduct. Wayland soon reduced required Chapel to a morning service in Manning Hall, whose graceful Doric pillars, now iconic, formed the porch for the University’s third building—a library and a chapel.

Dedicated in 1835 to memorialize Brown’s first president, Manning housed the University’s second sacred space, joining First Baptist Church (1775) built for “the publick worship of Almighty God and to hold Commencement in.” Sayles Hall (1881), with its glorious Hutchings-Votey organ and larger capacity, next hosted required Chapel until that practice was discontinued in 1958.

Rhode Island’s founder Roger Williams’ commitment to the “soul’s liberty” reverberated in Brown’s Charter: “all the members hereof shall forever enjoy full, free, absolute, and uninterrupted liberty of conscience.” Yet, Brown’s first ten presidents were Baptist clergy; and its by-laws required that the president be ordained and the faculty be Christian until that stipulation was retired in the 1920s. America’s rapidly diversifying demographics from 1880–1980 accompanied Brown’s adoption of the motto In Deo Speramus and a burgeoning visibility of that sacred hope on campus, including the late 19th century establishment of America’s oldest Roman Catholic fraternity, and campus lectures from learned clergy in Judaism, Christianity, Vendanta and Bah’ai. Hillel came to dwell on College Hill in 1951 and the Brown Muslim Student Association celebrated its 25th campus anniversary in 2014.

The Office of the Chaplain of the University emerged in 1953. From its inception its charge and crucial role was to ensure that a diversity of beliefs have voice and vitality on campus. Currently, a multi-faith staff, the chaplain and four associates—Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, and Muslim—provide spiritual care for the University family in all seasons of life, supporting religious identity and promoting interfaith understanding and religious literacy.